Ice Isn’t Nice

Ice Isn’t Nice

Flying for fifty years has taught me that it is not a question of if something potentially dangerous will happen, but only a question of when and the quickest way to invite hazards is to let my guard down – to leave something unattended. My very first lesson in this was observing a U.S. army chief pilot training an Ecuadorian student at Fort Clayton Army Airfield, Panama in 1967. While I worked on the flight line the two got into a Bell OH6 helicopter with no apparent preflight safety briefing or review of their flight plan. The chief pilot switched lights on, started the engine and then advanced the throttle to full power. The Bell then rose to about 100 feet away from the hangar. From my view as the machine hovered about 70 feet above the tarmac I could see a lot of talk going on within the bubble. It began to look a lot like a modern day political debate where fists are the only thing not raised.

To my surprise, with the student now on the controls, the helicopter rotated counter clockwise 360 degrees left and continued to do so at an ever increasing rate. On each revolution it appeared the two pilots were arguing more intensively. It appeared the chief was trying to get control but the student held a death grip and he wouldn’t release them. The Bell was now spinning like a top and the chief pilot grew ghostly white while the student continued yelling – in Spanish. Now exceeding its flight envelope the aircraft came crashing down. It hit the pavement hard flattening it on impact to a little more than half its original height. Like King Kong’s fist, the rotary wing then crashed right through the cockpit smashing and crushing the Plexiglas. It stopped centered exactly between the legs of the two pilots. With no fuel leaks and no fire, both occupants got out of the wreckage and walked away dazed shaking their heads. The fact that they survived unscathed was nothing short of a miracle. God knows they were so lucky that day, but who wants to bet on luck? A slightly different flight action by either may have ended in death. This all could

have been prevented by some comprehensive preflight planning including Cockpit Resource Management, CRM.

Fast forward to July 29, 2016, I’m in the left seat of my home built Super Seawind flying at 17,000 feet returning to Hanscom Air Force base from Oshkosh Airventure. I was about to learn a new page in Murphy’s Law!

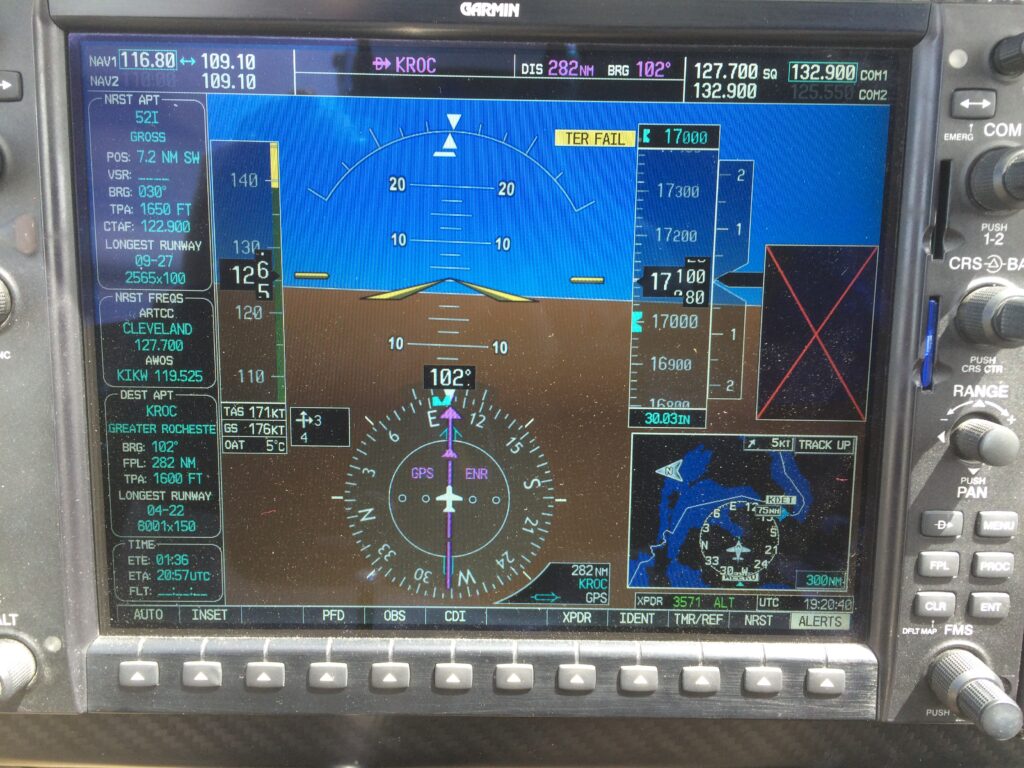

We were flying IFR in and out of clouds. No worries: It was 5 degrees Celsius. We were less than an hour and half from Rochester our next and final fuel stop. The autopilot was tracking true giving us 180 – 190 knots true airspeed. Not bad, for a four-seat amphibian I mused. Seeing clouds ahead I switched on the left and right wing pitot heaters; one for the separate G900x and one for the Grand Rapids flight control and Engine Information Systems, EIS. Miles later we were in and out of the clouds. Ah, just relax and enjoy the ride, I thought. Then there was a thud. It felt like something small had just hit N71RJ – but from where? With zero visibility we couldn’t see anything outside. Then momentarily out of clouds we could see the windshield had begun to frost. Herbert Drury, CFII, copilot, pointed and said what is that? In my 80 or so hours flying my self-made Seawind I had never seen anything like it before. With an OAT of 6C, I thought it might be some temporary frost. After all it was too warm for ice, right? A glance at the bare leading edges of the wings reinforced my erroneous thinking. Seconds now seemed like minutes.

Sensing nebulous danger, my heart rate fired upward. We were back in the clouds and then; thud! Emerging from clouds I got another quick look and both wing leading edges were icing up fast. I glanced again on indicated air speed. It had declined 5 Kts in about 30 seconds. “Ice on the wings” I called out. Herb immediately called Cincinnati center and we were assigned 11,000 feet. I switched off the Trutrak autopilot and began a descent. Those thud sounds were the five blade MT propeller spinning at 1900 RPM throwing bits of rime ice onto the wing. By the time I leveled off, all the visible ice was gone. All was quiet once again. The PT6 again purred along like a trotting tiger.

Lesson learned: 80% of what happens, good or bad, during a flight has a direct relationship to preflight planning. Flight planning and CRM may have saved this day, but what else could I have done to make our flight even safer?

Yes, the seconds saved by splitting cockpit duties for the entire route when seconds really mattered considering the fast build up of structural icing may have saved us from far graver consequences – and limited options. Herb was immediately on the radio and I was on the controls guiding my composite ship to safety. Flying on my toes again reminds me that one of my biggest foes is complacency. I hadn’t anticipated an icing scenario in preflight planning. Next time I’ll anticipate icing when the environment includes up to 8 degrees Celsius and if my amphibian is to enter any moist environment. Considering that N71RJ could fly even thousands of feet higher than FL 170, I’ll certainly include above the clouds altitudes in my future flight planning too.

What saved us from a bad outcome is the difference Herbert and I made. Unlike the Bell pilots I had observed with horror in 1968, Herbert and I used CRM before and during the actual flight. Although we thought we would have the safest ride possible, I missed something important. Never again! Next time I’ll add icing, altitude rates of climb per my airplane weight and balance performance chart and all altitude options available to me before getting into my Super Seawind.

ALSO READ 7 Ways I Make My Seawind Fly Safer